This image will become important later

Posted by <Thomas Mader> on 2022-10-15

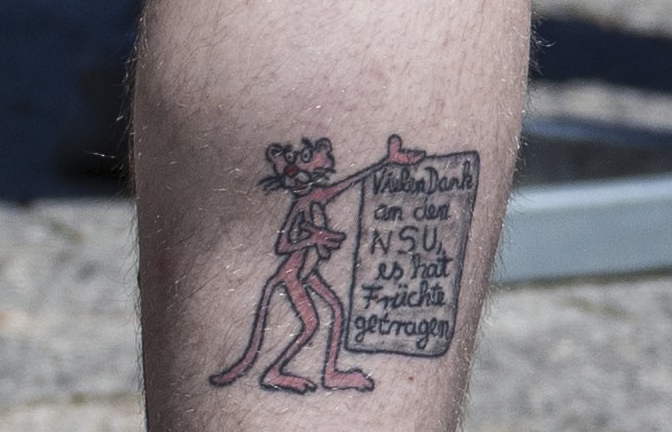

Pink Panther tattoo on Neo Nazi, photo taken during far-right rally in Germany by Nico Kuhn (2020)

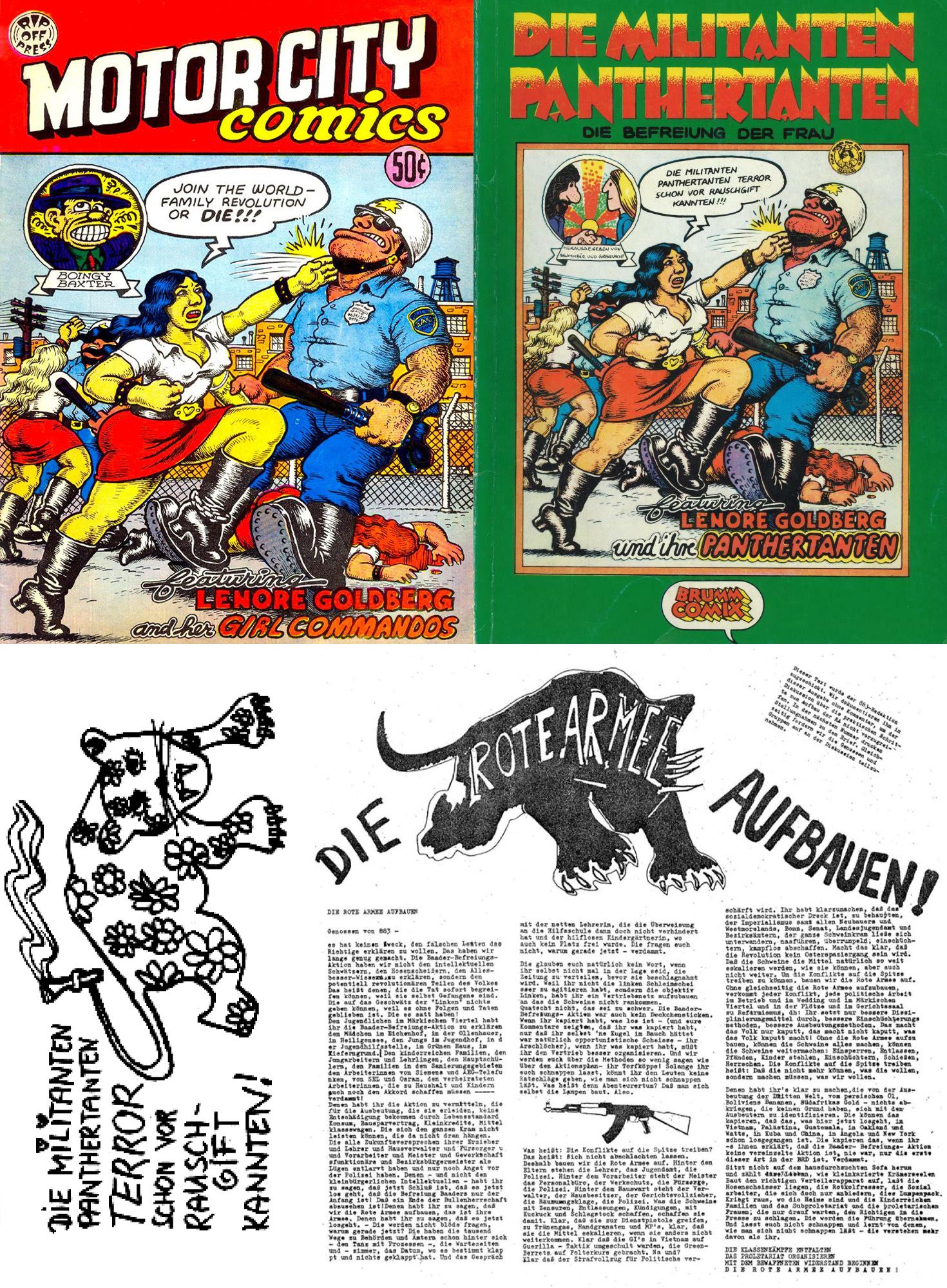

Top left: Robert Crumb publication “Lenore Goldberg and her Girl Commandos”

Top right: German translation > “Lenore Goldberg und ihrer Panthertanten” (Lenore Goldberg and her panther gals); “Join the World Family Revolution” translated to “The militant panther gals knew terror long before they knew hard drugs”

Bottom left: Sticker designed by women from the anarcho-liberatiran Agit 883 editorial collective (ca. 1970) using the same line from the German translation of Crumb’s “Lenore Goldberg and her Girl Commandos”

Bottom right: Article in Agit 883 “Build up the Red Army!” using potentially US-inspired panther imagery (ca. 1970)

digital collage “dig site”

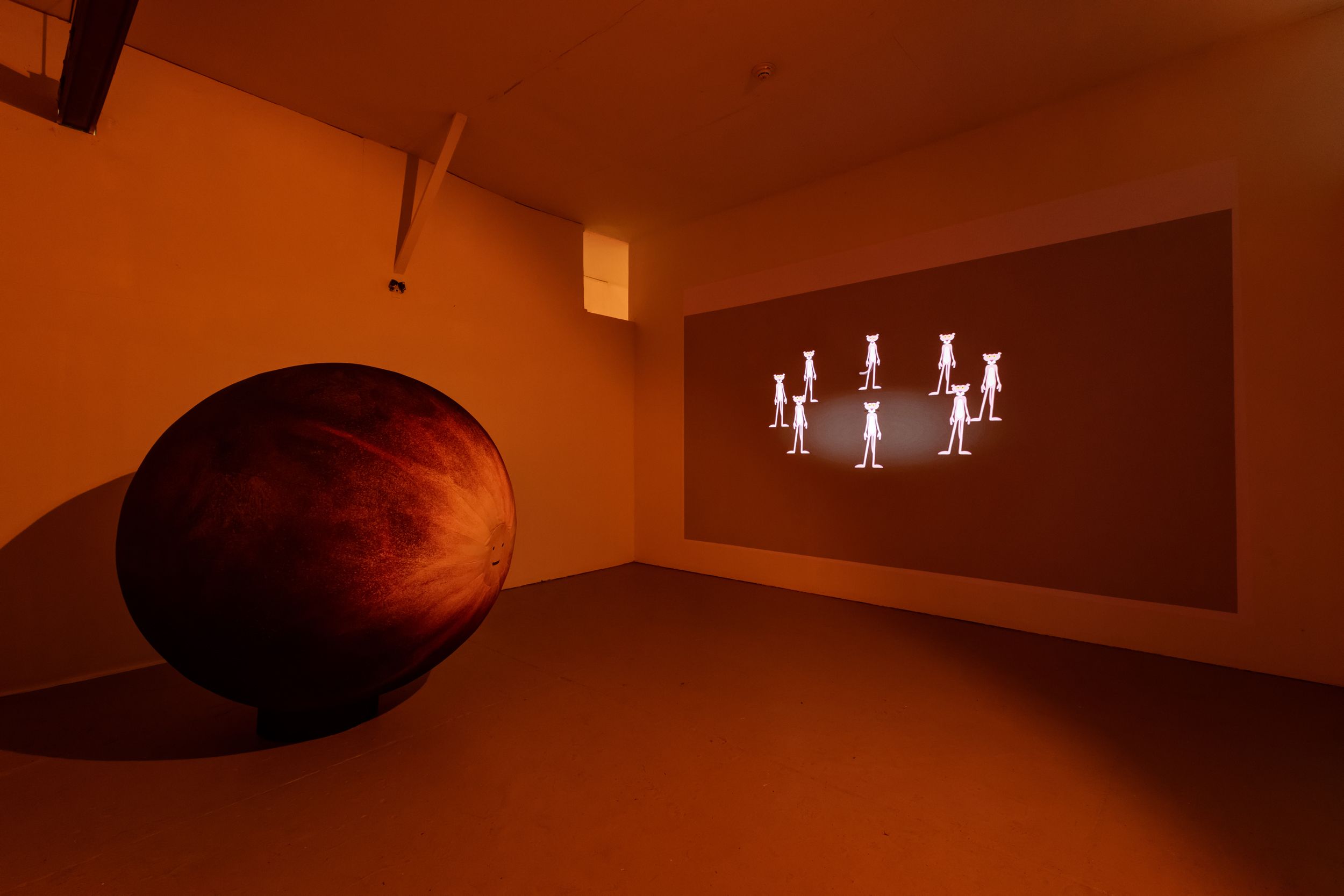

installation view “all heat and no light”

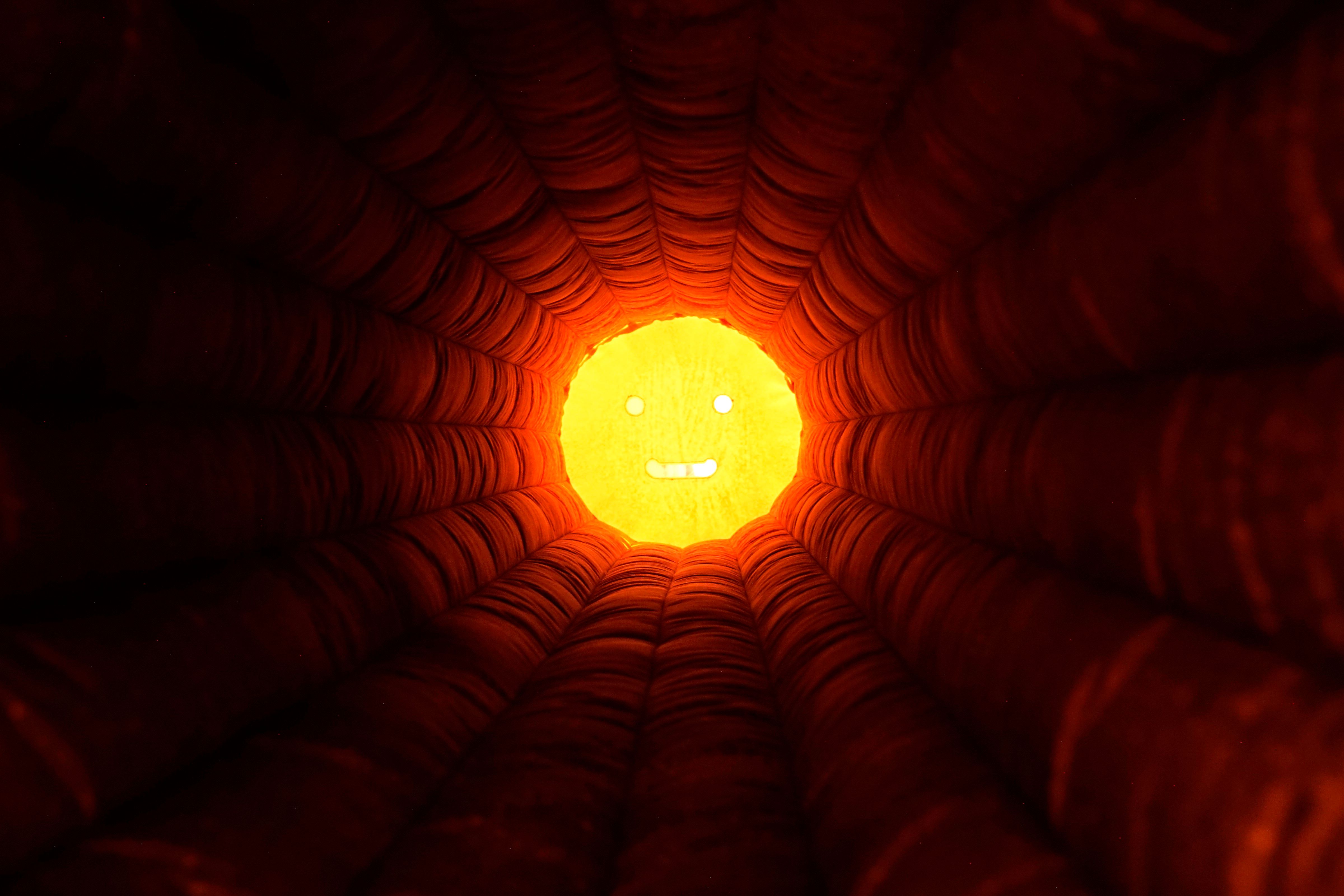

inflatable sculpture interior view

Still from “all heat and no light”

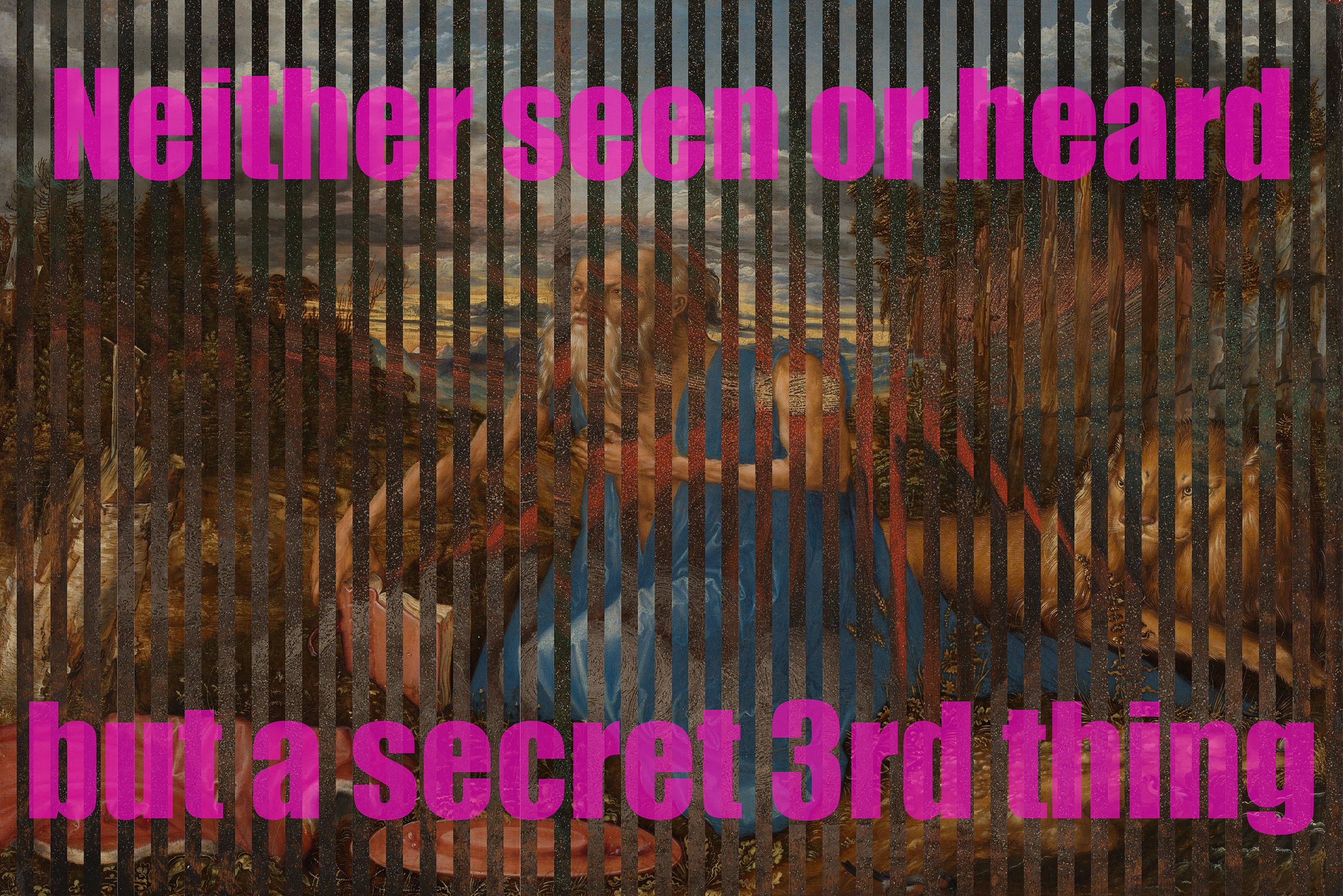

digital collage “neither or”

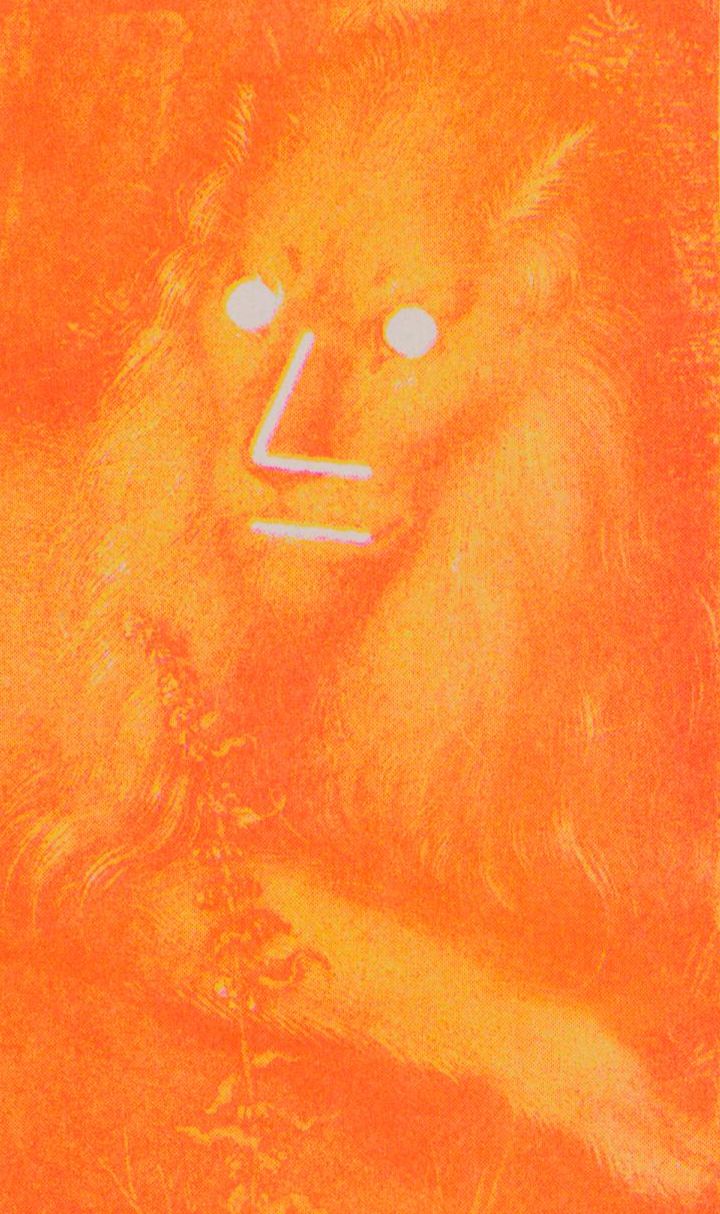

riso print Durer lion NPC

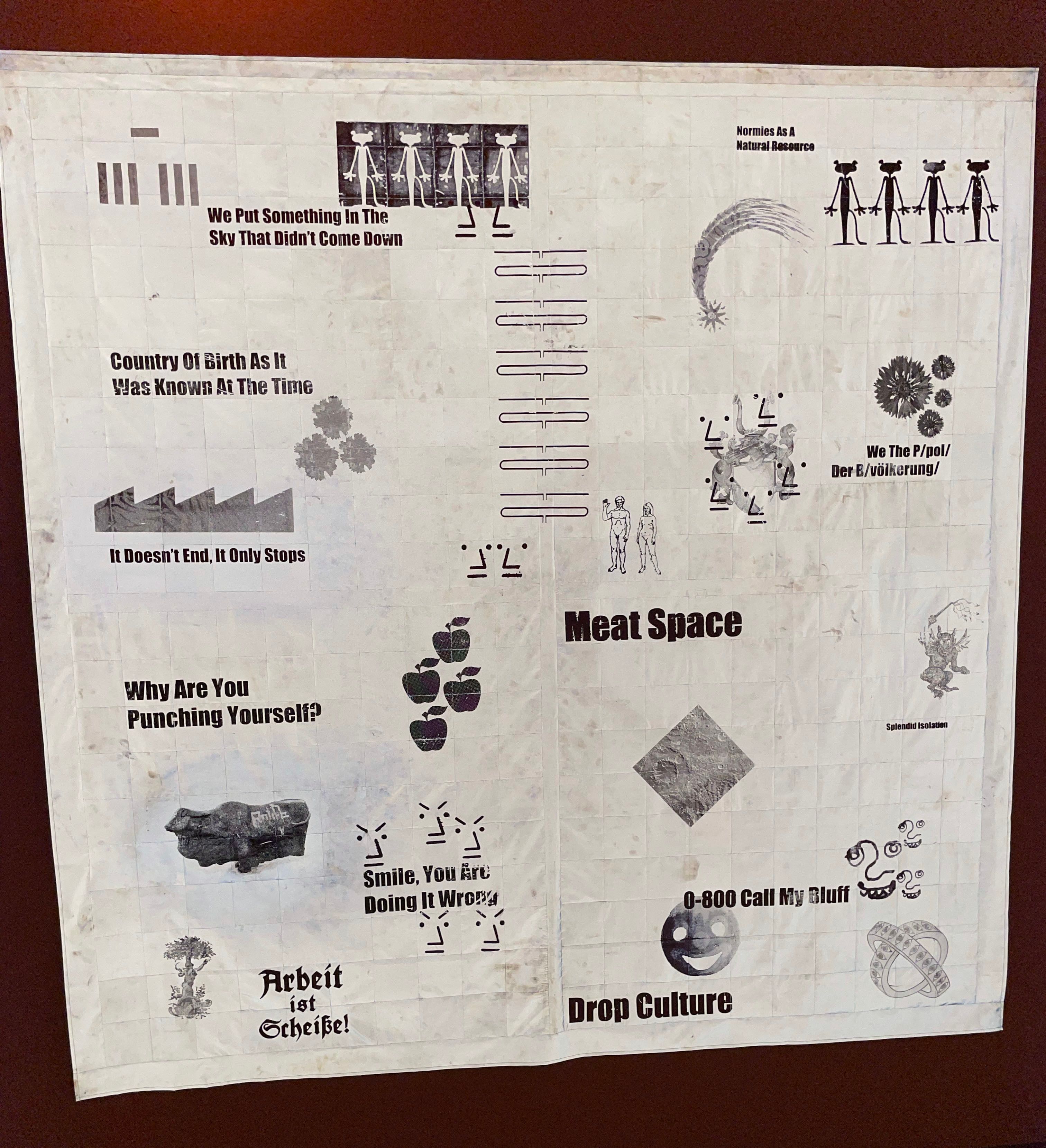

retro reflective quilt with screen print

digital collage “ways in, ways out”

all heat and no light, animated video loop, 8 min.

In November 2011, after an over 12 year long killing spree, the existence of Neo-Nazi terror cell NSU (Nationalist Socialist Underground) was first reported on by German mainstream media. Two of the three core members of the cell had just previously died in a gas explosion inside a camper van under mysterious circumstances. Soon after the uncovering, the last remaining core cell member mailed out a video to Berlin-based anti-fascist archive APABIZ in which excerpts from the Pink Panther cartoon series were mashed up with TV footage reporting on the crimes committed by the cell.

The mash-up tape was first sent to the archive, presumably because the cell members didn’t trust mainstream media outlets and thought that this independent institution was the least likely to succumb to concealment requests by the German government. The archive proceeded to sell the tape with exclusivity rights to the highest media outlet bidder, German news magazine “Der Spiegel”. An antifascist archive was essentially handed a blank cheque by a neonazi terror cell. After the exclusivity period expired the archive distributed the video to all interested media platforms. My request to talk to an archive representative about this process was politely denied.

A pink feline trickster in constant conflict with authority is a perfect blank canvas for an extreme political agenda. Even though the German far-left, possibly influenced by US panther imagery, had already used panther drawings for flyers and posters in the 60s, it was ultimately the far-right that successfully appropriated the image material. Even though the outro song from the German version of the cartoon can still be heard playing at far-right rallies, the panther never reached full mainstream legibility as a hate symbol in Germany, unlike Pepe the Frog, who was included on the US Anti-Defamation League’s list of hate symbols in 2016. The Pink Panther thus can be understood as a digital ancestor to Pepe. It serves as an example for how apolitical image material can be adapted with limited technological means, charged in a clandestine and secluded environment, and made palatable for a way of reading that resonates with the mainstream.

Although officially prohibited, many residents of East-Germany watched West-German TV broadcasts and there was a chance the core members of the terror cell, all of which were born and raised in the former East-Germany, had seen the Pink Panther on TV while growing up. The western state-run broadcasters took measures to cover as much of East Germany as possible by building high powered transmitters close to the border and especially after the end of WWII and during the Cold War the US was heavily interested in bringing its products to the West-German market and to use pop culture as a soft power tool. The only parts of Eastern Germany that had difficulties receiving these broadcasts were the very north-east and the very south-east, which were consequently dubbed “Tal der Ahnungslosen” (valley of the clueless).

The shock from seeing the panther seemingly inseparably bound to Neo-Nazi ideology originates from the character’s place in a collective cross-generational German memory. The character was originally created as a gimmick to make the opening and closing credit sequences of the US Pink Panther movie franchise more enjoyable. The credits text did not directly relate to the panther and the character first and foremost existed in a space defined bytext. Through the characters' appeal and by demand of the audience, it was separated from the textual space and given its own visual space. This visual space was then again given text (the German version of the cartoon features a voice-over in rhyme form), so while at first the panther related to text, text now relates to it, making it a perfect example of what Mitchell and Boehm call the “visual turn” or “iconic turn” respectively.

Fascism is flexible enough not to rely on old symbols when its supporters can’t use them anymore. Baudrillard coined the term “heavy signs”, for events such as death, tragedy, and catastrophes. It was his understanding that these signs are not subject to the same erosion of meaning that all other signs go through. Pop culture on the other hand promotes the idea that all images and texts are up for grabs, can be dealt with playfully, and are fair game for reapplication and distortion. Complex issues are being flattened into bumper sticker truths, layers and layers of irony are used to disguise dehumanizing opinions and violence in cartoons has no consequences until it does in the real world. Along with the human catastrophe, the semiotic one comes sneaking in.

In 1492, of all years in recorded history, a meteorite struck the earth's surface outside the town of Ensisheim in what is now France. The impact was seen and heard for hundreds of miles and the townspeople had to be stopped from immediately breaking the stone up into countless small fragments by German King Maximilian I’s representatives. The king, on a military campaign against France, appropriated the powerful image and declared the event a good omen for his current military campaign against France. Poet and propagandist Sebastian Brandt produced illustrated leaflets depicting the impact in support of the king’s war and spread them throughout Europe. After the campaign was won, Brandt rehashed the exact same leaflets for the king’s new campaign against the Turks.

Without having witnessed the event himself, Albrecht Dürer, a contemporary and collaborator of Brandt and working under the patronage of Maximilian I, painted an abstract version of the impact on the back of his version of “St. Jerome in the Wilderness”. Works depicting St. Jerome were popular at the time and had been painted by Leonardo and Mantegna, amongst others. St. Jerome and the meteorite had both become memes.

In 1942, German writer Thomas Mann, who had still supported the German war efforts in WWI, exiled to California, living in a villa that is now a German state-run art residency, and refused to “apply the term ‘historical’ to this monstrous phenomenon”. In his novel “Dr. Faustus”, an appropriation and re-working of the classic Dr. Faustus myth, popularized by German writer Goethe, he tries to reclaim Dürer from the firm grasp the Nazi party’s propaganda apparatus who themselves had appropriated the painter and had deemed him “the most German of artists”. He expresses his opposition to Nazism the only way he knows how: by navel gazing, reclaiming, publishing, distributing and betting on an audience. Alt-right meme creators often launch vicious attacks against anyone trying to recontextualize image material they deem “theirs”, which raises questions about the possibilities of reclaiming images that have been branded “far-right”, if there is ever a way to shed this notion, if that is even desirable, and what the time frame for such an undertaking is.

In 2020 many Covid-deniers and anti-maskers could be seen marching side by side with hardcore Neo-Nazis, later claiming not to know about the symbols and slogans present at the marches, amongst them the before mentioned Pink Panther theme music.

The described timeline shows that the foundation of interpreting text and image material and the effects of said interpretation on real life events has essentially stayed the same. Memes play an important part in the coordinated actions of social movements in that they are personalized and adapted by individuals to tell their own stories. The imagery itself is often not loaded with any inherent political meaning, and figures as a perfect canvas that is just waiting for a selection of words to give it a specific charge. Meme creation is an ongoing community effort that on its surface might appear fractured and at times random, but the conversation, while not unified in its message, is coherent.

By printing, Dürer took images from inside the church and brought them into people’s homes, but his pieces still came at a price.

Mann wrote novels that are considered high culture, but definitely not mainstream.

The German police towed the terror cell’s van over a ramp onto the back of a truck so it could be brought to a safe location for forensic examination. The towing resulted in all liquids shifting inside the vehicle which destroyed nearly all evidence.

The cell’s supporting network remains largely intact, the muder victims’ familie’s demands remain largely unheard.

We have heightened accessibility to source materials, but visual and textual literacy are still lacking. The valley of the clueless seems to live on quite willingly. We are the accelerated containers with liquid sloshing around inside, trying to catch up with the new speed level. Things are moving very fast, meteorites and panthers are made to speak, and words are continuously trying to shape images.

Bibliography

Brooks, Michael (2020): Against the web, zero books, Hampshire/UK

Bülow, Lars & Johann, Michael (2019): Politische Internet Memes, Verlag Frank & Timme, Berlin/Germany

Burda, Hubert & Maar, Christa (2005): Iconic Turn: Die neue Macht der Bilder, DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne/Germany

Citarella, Joshua (2019): Politigram & the Post-left, self-published, USA

Hoare, Philip (2021): Albert and the Whale, Pegasus Books Ltd., New York/USA Jazo, Jelena (2017): POST-NAZISMUS, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld/Germany Metahaven Collective (2013): Can jokes bring down the government?, Strelka Press, Moscow/Russia

Nagel, Angela (2017): Kill All Normies, zero books, Hants/UK

Shaw, Jon K & Reeves-Evison, Theo (2017): Fiction As Method, Sternberg Press, Berlin/Germany

Shifman, Limor: Meme (2014), Edition Suhrkamp, Berlin/Germany

Rohrmoser, Richard (2022): Antifa, C.H. Beck, Munich/Germany

Von Gehlen, Dirk: MEME (2021), Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin/Germany

Watson, Mike (2019): Can The Left Learn To Meme, Hampshire/UK

Woods, Heather Suzanne & Hahner, Leslie A. (2019): Make America Meme Again, Peter Lang, New York/USA