Cultural Work is Not the Problem

Posted by <Max Lopez> on 2021-04-19

Cultural Work is Not the Problem: Moving from Essentialism to Critical Consciousness

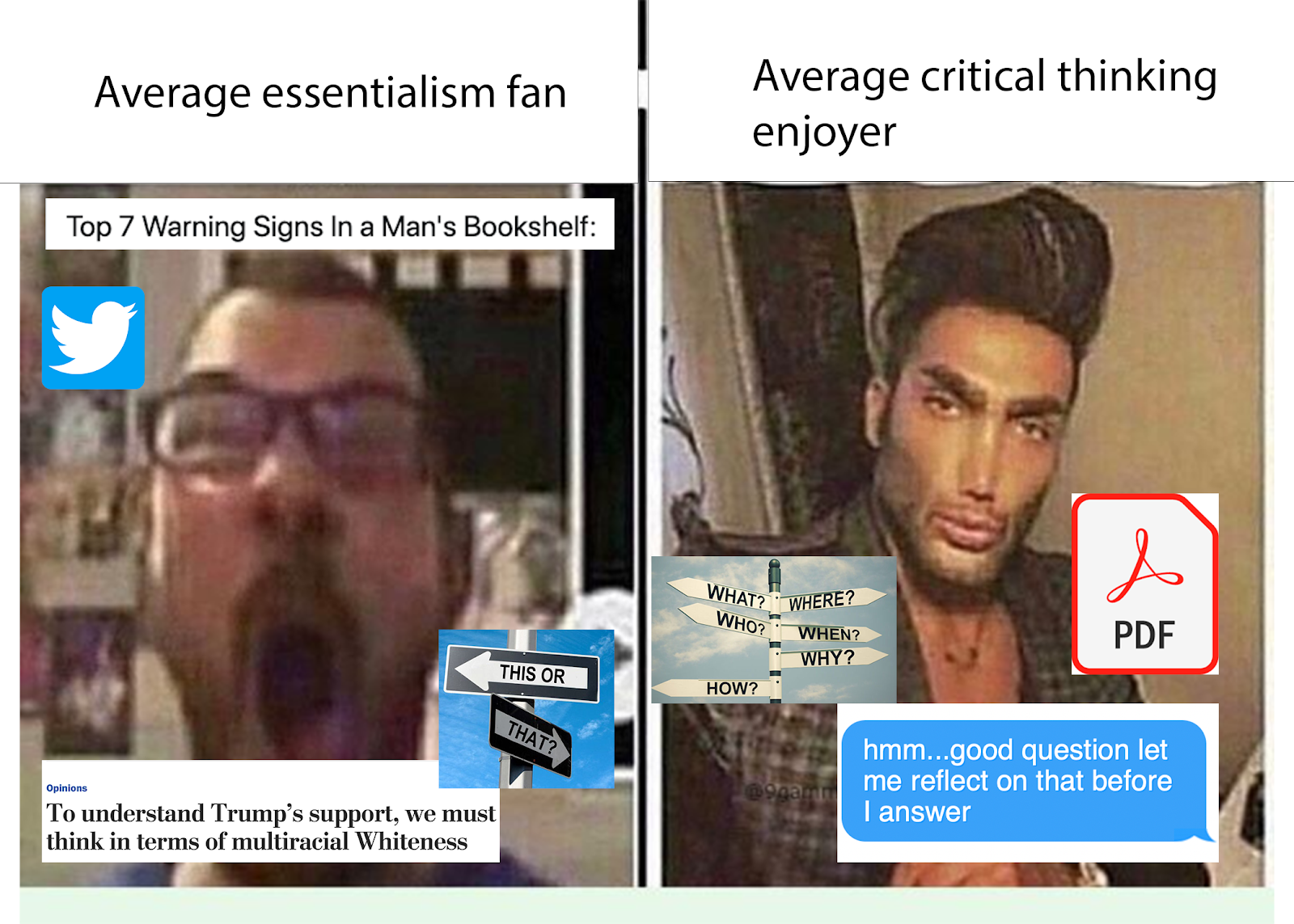

Internet memes are a significant, if hotly contested, aspect of political formation for the politically inclined, disaffected and extremely online. Increasingly, it seems that all of us, regardless of political persuasion or manner of engagement, need to come to terms with the ways that memes have remapped both our discursive framework and our real options for action. Instagram and YouTube provide venues for an overwhelmingly young user base to try on and discard a dizzying array of ideological costumes as they struggle to explain the world to themselves and to their peers. The anonymous forums 4chan and 8kun fostered the loosely-organized Q Anon movement whose adherents featured prominently in the January 6th Capitol Building riot. The same platforms transformed Pepe the Frog from an indie comic book character into the focus of mainstream liberal handwringing as a right wing hate symbol. On Twitter, emojis ranging from snakes to donuts began signaling allegiance to one political persuasion or another. Clearly there is a relationship between memes and politics as it is lived.

Relatively few users will spend the time or energy necessary to effectively decode the wide variety of symbolic orders on the web. At the risk of (ironically) reducing all our problems of hyper-signification, dysfunctional communication, and compulsive behavior to just a single factor, one thing the Left must understand is the pernicious effect that essentialist thinking conveyed in memes and messageboards is having on our discourse communities. The resulting elimination of context and nuance creates a vacuum that draws in imperialist thought--domination and reaction; hierarchies and repressions. This dynamic is especially paralyzing for the online Left because a reductive packaging of ideas is so often the vehicle for messaging that is ostensibly anti-racist, gender liberationist or toward class solidarity. Our efforts toward building a viable organized Left cannot move forward by these means precisely because their “either/or” frameworks are fundamentally incompatible with transformative and anti-authoritarian politics.

Still, commentators disagree on whether or not it is apt to draw a causal link between posting and organized action taken in the world. Some suggest that posting about politics is on balance a busy-box that occupies the public while they are fleeced by an unaccountable ruling class. Artist and researcher Joshua Citarella has spent the last several years documenting and analyzing the way that algorithmic social media “funnels” its users toward radical “e-deologies” including anarcho-primitivism, monarcho-syndicalism, and authoritarian communism, to name just a few. What distinguishes “e-deologies” from other forms of political thought is that so many of them lack practical expression.

Not just daily, but many times a day, people around the world refresh their browsers hoping for something different. We are hoping for relief from all the feelings produced by both extreme precarity, and by our inability to influence elections or any other aspect of "democratic" government. The U.S. government is frozen by bi-partisan corporate capitalist consensus while many Americans are fragmenting into ever-smaller groups defined by aesthetic concerns. When we post and respond, we are at least doing “something.” In the absence of organized influence from the bottom up, the activity that many of us refer to as politics has become primarily a contest over cultural signs and symbols, commonly referred to as “culture war.” Meanwhile, as we continue to puzzle over which combination of factors might lead internet radicals to bring their ideas into the streets, a grim political gridlock continues to be the order of the day.

Our confinement to this arena is also subject to (our own) critique: we berate ourselves and each other for being so weak that we can only manage to pick over the symbolic scraps or pick on each other, while “the real” situation of our lives rages and hurtles on. But we shouldn’t be discouraged from working to clarify the role of cultural politics in sustaining individual hope and building the capacity of our beleaguered left wing organizations and institutions. Cultural analysis and debate are not beside the point; they are inseparable parts of making material interventions in our lives.

The real issue is how we’re going about our projects of cultural analysis, and for what purposes. Ultimately, to be successful in this project of producing and crystalizing left wing culture, what we need to do is reject the reductive dominant value of essentialism: the certainty that everything can be understood as distinct collections of innate characteristics, and that the world can be sorted into bounded categories. Unexamined and unaddressed, this tendency will lead us not only to remain locked in our siloes of thought and to confirm our own biases, but to reproduce the same self-defeating dynamics of neoliberal or reactionary ideology in much of our own thinking and nascent movement-building. It’s the looping, self-defeating, self-consuming, paralyzing logic of essentialism that hamstrings us, not the work of analysis nor the focus on culture. “Memes” as a cultural form are not necessarily defined by essentialism, but many of them work by way of that logic, so we need to understand their attraction, and types of humor and pleasure that may actually erode potential for common ground.

Crisis of Meaning, Disappearance of Irony

We face a crisis of meaning as surely as we face climate catastrophe, and the political establishment is taking advantage of these crises to shore up its monopoly on meaning itself. In the age of pandemics, runaway environmental mismanagement, and festering social atomization and alienation, it is impossible to imagine successful organizing that does not include a space for cultural expression, especially humor and irony. Many of us turn to the internet in a desire to participate in transgressing the boundaries of expression deemed “acceptable” on the terms of a stifling “culture war,” yet our ability to build mass-based political power risks being stymied by the tendency for humor and online communities to become insular. Too often we fall into a reliance on in-groups and out-groups and unintentionally reinforce the very divides that we must bridge to create viable left coalitions. On a recent episode of the New Books in History podcast, Chapo Trap House co-host Matt Christman offered that “everybody who got mad at irony [is] mad at connotated meaning.” When we have interactions mediated by social media, he argued, jokes and conversations have their context stripped away. Without shared cultural touchstones, irony and humor more generally become illegible to a wide audience because these forms rely on the subversion of shared expectations. In a connotative vacuum, jokes that parody a right wing perspective can fall flat; at worst, the same jokes run the risk of being read by the uninitiated as espousing the very reactionary views they intend to skewer.

Illiteracy and the Empire of Essentialism

This breakdown of shared connotations results in many uncomfortable scenarios that anyone spending time online will be familiar with, ranging from simply not understanding a meme, to being upset by a joke mistakenly taken at face value, to the dreaded experience of being baited into engaging with trolls. Those of us who are emergent social media natives know that venturing into unfamiliar corners of the web requires a certain wariness and an ability to decode complex and rapidly shifting systems of meaning almost at a glance. When common ground, time and space are all in short supply, the memes that tend to go viral are those that fit most neatly into the dominant cultural value system, notably essentialism. Although this way of thinking existed before and exists independently of the internet, its reductive framework is encouraged by frequently surface-level engagement on social media, making it difficult to create and sustain the virtual communities of belonging many of us come to the web seeking in the first place.

Leaving the Discursive Locker Room

Even in our current era of marketized diversity and inclusion, memes will continue to enforce the boundaries of hegemonic identity unless their creators find ways to subvert essentialist thinking itself. The “boys vs. girls” family of viral memes are a prime example of our frequent failure to break with reductive thought, with iterations ranging from “boy’s locker room” to “men with a time machine.”

The most common version of these memes reinscribe hegemonic cis gender roles, such as by representing the girl’s locker room as polite and mundane in opposition to the war-like chaos that characterizes the boy’s locker room. They are effective because they are funny and operate on multiple symbolic and political levels, prompting the viewer to say, "so true.” What is particularly interesting about them is that the girls are "appropriately" limited to the realm of text in the locker room, while boys are occupying a colorful space of legend and blockbuster action films like Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings. Boys are the feature, while girls are becoming acclimated to a life “on the bench." Decades of research suggest that gender roles are learned rather than inborn and that sites like school locker rooms are places where gendered behavior is performed and policed. As funny as it is, the meme’s humor originates in an essentialist stereotype that ultimately constrains the horizon of accepted gender expression. The most incisive of these memes point out and even destabilize patriarchal gender binaries, but the popularity of these memes indicate the ongoing influence of essentialism on our thinking, whether we are aware of it or not. Memes, like locker rooms and like all of culture, remain a site of struggle over whose meaning matters most.

The Only Way Out is Together

Scholars such as Mark Fisher argue convincingly that many of us have implicitly forfeit this struggle. The neoliberal politics of essentialized identitarianism that form the basis for “culture war” are a tacit acceptance of ruling class control, which he calls reflexive impotence. It is increasingly difficult to ignore the compounding crises of imperialist-white supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy, but the assumption that no alternative system is possible or even desirable has proven dishearteningly resilient. In his prescient 2013 essay “Exiting the Vampire Castle,” Fisher describes the “Vampire Castle” of neoliberal identity politics as a labyrinthine hall of mirrors, where all efforts to reach across the boundaries of difference and build class power among the oppressed comes to a dead end and we are each left facing our own reflection: utterly alone. The denizens of the castle enforce its rules: individualize and privatize everything, make thought and action appear difficult and undesirable, propagate guilt, essentialize, and, finally, think like a liberal. Essentialism, in particular, makes it possible and necessary to disarticulate class from race and gender. This discursive and social space is clearly authoritarian and extractive, so in order for the participants to pass themselves off as left or “progressive,” they must punish every perceived slight and deviation from this essentialized thinking or risk their group-think being exposed.

In his work, Fisher relies in part on the tools of cultural studies developed by Left scholars such as Stuart Hall, bell hooks and Robin D.G. Kelley. Like Fisher, these intellectuals insist in their work that race, class, and gender must be examined and critiqued as inseparable interlocking forces. They help us to understand that Left mass political movement has historically been undermined by an overemphasis on essentialized class unity when it relies on the reduction, or worse, the erasure, of difference.

Both/And/Maybe

Patriarchal gender roles and white supremacist racial hierarchy have proven so persistent in part because they purport to explain and justify visible differences among people, such as skin color and gendered bodies. We can see how these categories and hierarchies have bedeviled the crucial project of building class solidarity. Western European-inspired Marxist theory has struggled to move beyond a universal concept of the proletariat that is assumed to be white and male, and beyond a reductionist notion of class struggle as occurring solely between owners and non-owners of capital. Left political analyst Matt Bruenig argues that this flawed analysis leaves out the mass of non-workers, including children, retirees, and the unemployed. Meanwhile, cultural resistance to “color-blind” racist and neoliberal “equality” discourse since the 80s and 90s has also become not just much more “identitarian,” but more explicitly dedicated to explaining, justifying, and emphasizing visible differences among people. When we engage seriously with the work of authors like Fisher and hooks, we find that it is fruitless and misleading to spend our precious time and energy slinging accusations back and forth of “class reductionism” and “identity politics.” Instead, we must consider these perspectives as being in productive conversation with one another. Indeed, it is the spectacular politics of the market that reduces these arguments to their least interesting and most easily coopted essence and pits them against each other.

The only way to escape this trap is for the Left to reunite a class analysis with the politics of race and gender. Certainly the bedrock of mass Left politics must be shared experience, it is just as true that the Left must be able to harness difference in the service of a common struggle against the interlocking dominant forces of imperialist-white supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy. Contrary to the reductive formulation suggesting that left politics must either be class-first or identity-first, Fisher’s manifesto against the authoritarian moralism of the “Vampire’s Castle” is entirely compatible with a class analysis that recognizes class as being segmented by other interwoven hierarchies. The enemy of mass based leftist movement must be correctly identified as essentialism rather than difference.

We all must struggle to expand the space of nuance and possibility--the alternative is giving into the group-think and bullying endemic to online echo chambers, whose logical conclusion is the uncontested rule of a global billionaire class. This is the true horror of the “Vampire Castle”: that we are each vulnerable to becoming our own prison wardens, tasked with policing our own behavior and that of our peers while the true managers of our misery passively benefit from our inaction. Work, housing, healthcare and education are contested space: they are both the parts of our lives where we are most clearly surveilled and exploited and the issues around which we must organize to build and leverage power. Similarly, the internet is largely a collection of private platforms where the average user struggles to maintain a semblance of control, yet they can offer the potential to form new collectivities that challenge the dominating influence of neoliberal markets. We cannot give in to a binary stance of either blissful optimism or nihilistic pessimism. Our best hope is to operate from a productive and ambiguous middle ground where the future is undetermined and contingent on a variety of factors, and where creative collaboration, and unique improvisation is possible.